Developing a Disaster Plan

Do you have a records management disaster plan? Headlines about natural disasters provide a stark reminder that we can’t control our environment. However, if we plan for disasters and assess risks, we can help ensure business continuity if disaster strikes.

To plan for disaster, analyze the different types of potential disasters and then prepare to mitigate loss. For a records manager, this means finding a way to limit interruption to vital records. It also means taking steps to mitigate the disaster’s impact to the records program.

Vital Records

You need vital records for your business to operate. Without them, you can’t continue to conduct business and you can’t determine assets and liabilities. For business to continue, you need to identify vital records and safeguard them from the impacts of disasters. This should be a major component of any disaster plan. You might, for example, keep vital records in a records management software and have the data backed up so you don’t lose any records.

Mitigating Disaster Types

A risk assessment should identify possible disasters, estimate their likelihood, and consider their consequences. This analysis allows you to develop plans as well as strategies to take if those disasters occur. Disaster likelihood varies based on several factors, many linked to location and climate. For example, the likelihood of a hurricane is greater in the Southeast United States than in the Northwest. Likewise, the likelihood of flooding is greater for locations in a flood plain. For companies with a centralized location, it’s best to have a disaster analysis based on that location. For companies with a larger geographic footprint, a high-level plan framework at the national or international level can help local branches develop local plans.

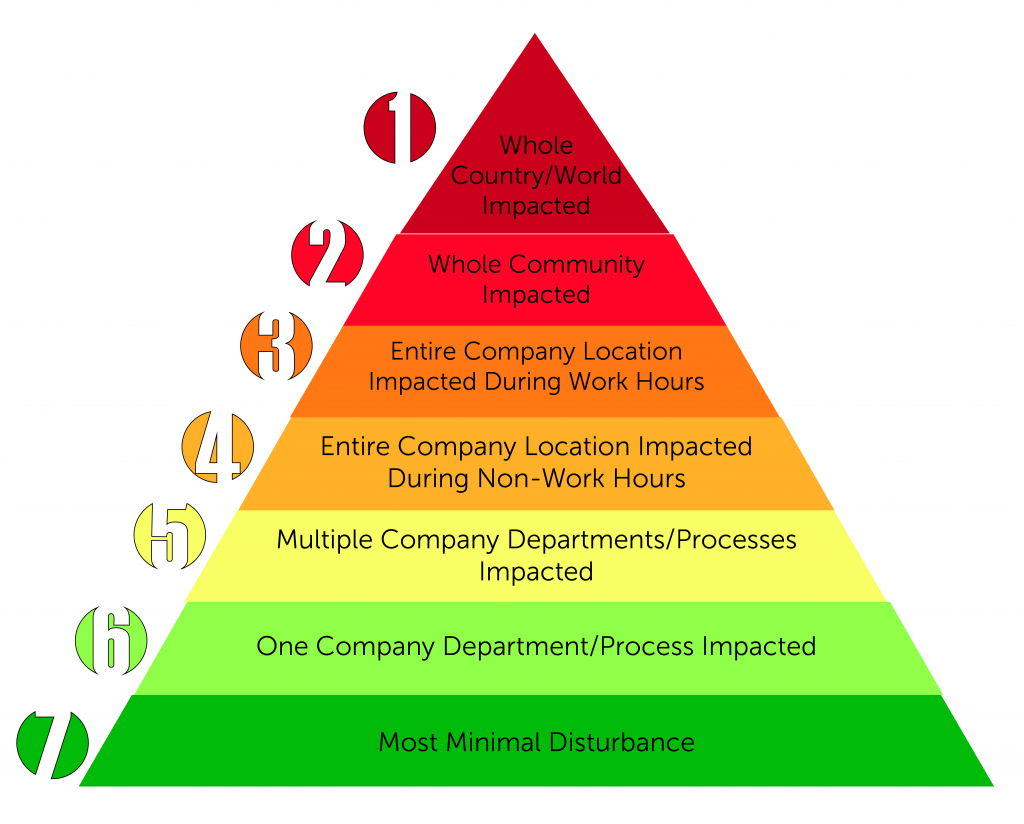

Whether a business is centralized, national, or international, Records Managers can use The Seven Classes of Disasters as a tool to brainstorm relevant disasters/events.[i] The classes encompass seven scenarios, which range from the most severe to minimal. You can see a simplified version of the classes in the chart below. [ii]

The chart allows you to brainstorm potential local disasters based on general disaster types. Then, you can develop and test procedures for each event. For example, if your brainstorming type 2 disasters and you’re located near a fault line, you’ll need to list severe earthquakes. Then plan to mitigate that event based on a risk analysis. It’s important that you develop procedures that include contingency plans to account for multiple situations.

Each step up in the scale indicates a more severe event, but the likelihood the event will occur decreases. This makes successful planning more difficult, more expensive, and less likely to be needed the higher you go up the scale. From a cost to risk perspective the best strategy to work around this is to plan from the bottom up. Your risk profile will guide how high up the scale you can cover. Typically, this doesn’t require spending a lot of time planning for a class 1 disaster. This is due to the high cost to plan, low likelihood the event will occur, and low success rate should that disaster happen.

Plan Enactment and Support

Even if your plan is perfect, if you don’t enact it properly, it’s not likely you’ll stabilize your processes after a disaster. You must coordinate logistics, implement the plan, and train so everything is ready before the disaster occurs.

Plan Review and Maintenance

While the risk of many of the larger scale disasters remains constant, many factors such as responses, technology, and personnel will continue to change. This means it’s vital to conduct at least an annual review and routine testing.

Conclusion

A good disaster recovery plan can be the difference between a company surviving a disaster or going bankrupt. Even with a solid plan, a disaster will likely result in recovery efforts, but the hard work and resources devoted to the plan act as an insurance policy. The key is to keep the business running and ensure you’ve defined the process for recovery efforts in the aftermath of the disaster.

[i] Mary F. Robek, Gerald F. Brown, & David O. Stephens, Information and Records Management, Document-Based Information Systems (1st Ed. 1996). Page 71, Table 4.1.

[ii] Modified from Id.

Disclaimer: The purpose of this post is to provide general education on Information Governance topics. The statements are informational only and do not constitute legal advice. If you have specific questions regarding the application of the law to your business activities, you should seek the advice of your legal counsel.

Author: Rick Surber, CRM, IGP

Senior Analyst / Licensed Attorney